Overland

Singing on Country

A strong and sweet reminiscence by Buluwai Traditional Owner, Cultural Custodian, and musician Willie Brim about how he started playing music and putting Indigenous people's struggle and their culture into song.

‘You call us activists. You call us freedom fighters. We didn’t wake up one day and say, this is what I’m gonna be. If it wasn’t for love of country, of our people, for each other, the land, the waters, the animals. We’d just wither away.’

While we were on Twitter

'Two red balloons were extracted from the swollen belly of a grey-headed

albatross | A marine biologist found a barn owl, face in the sand,

next to a half-eaten rat | Not far from Adelaide, an Australian

gannet drowned in a fishing net | A magpie strutted back

and forth on the bitumen beside his flattened mate'

An audio recording of this poem aired on ABC Radio National last week.

WRITER & WRITER: The future of swans

AZ: What Bella Donna brings with her, and this is a driving force in the book, is swan lore, the extraordinary stories of the swan that play out in so many cultures worldwide. How did all of that emerge?

AW: She has a lot of knowledge of swans, white swans, but there are eight different species of swans in the world. I also wanted her character to show that we are all in the same boat, in a way, and things can happen to any of us, so we should be careful of how we treat one another. In one of his essays, Calvino also quotes Borges saying that there are many men flying in the air and many men on the ground and on the sea, and what happens to them happens to me. And this is true.

The Australian Publishing Industry’s Problem with Class

'Too many of these types of stories come from people without any basic understanding of the lives of working class people, and without more working class people telling their stories themselves these realities will remain either invisible or unfairly portrayed.

What we are seeing anew in this pandemic is that the working class is a large, diverse and complex community that rarely gets heard or understood. It is the beating heart behind the scenes of the nation, doing some of the hardest and most essential work and not only getting disproportionally rewarded for it – but paying the biggest price when things go wrong. The least we can do is listen to its stories, and do this up close and personal.'

What makes an icon? On the design and disposition of Sydney’s architecture

'The thesis of the following essay struck home,' writes Ben Etherington. 'Particularly, that the Barangaroo casino is an icon of an unregulated market that is parasitic in its very form on the icons of the past created by public investment. I think of it every time I look at the building, which, unfortunately, is unavoidable!'

'The Australian ugliness is not the absence of beauty; it’s only partly an aesthetic question. It is the lack of strong design principles, the Featurist impulse to distract and dazzle rather than develop cohesive responses to the competing functional, economic and aesthetic demands we make of architecture, responses that should service the current needs and future aspirations of users. How could such a significant redevelopment of public land be so skewed to the interests of one party?'

The disappointments

At my age, the dust of my own mortality falls upon me from dark and waiting stars and there could be much to be disappointed about...I could be disappointed that, even now, most of my writing goes down like a lead balloon, that I do not own my own home, that I am not yet a critically successful novelist, that The Drum does not invite me to share my senseless opinions with other senseless opinions, that This American Life has never called to tell me Ira Glass wants my life, that I have forgotten what it is to live in the countryside...

Hand on heart

Many Noongar parents wrote letters to Neville, pleading for the return of their children. Some children even wrote to him, pleading to be returned home. These letters restore some humanity to the inhumanity of those periods, a time of stolen children and stolen futures.

One of these histories belongs to my grandmother’s grandfather, Edward Harris. He campaigned for more than a decade, between 1915 and 1926, for the return of his four children, Lyndon, Grace, Connie and my great-grandmother Olive. Harris corresponded with Neville on numerous occasions. Often his emotions linger in his words, or in the handwriting, or in other marks on the page.

Against Efficiency

This very necessary essay delves into the history of 'efficiency' as a concept and management tool, looking at how principles once vaunted as a means of freeing up time have morphed into a mindset that demands we use our free time to labour.

We are not living under twentieth-century Taylorism anymore, but an internalised version in which we ceaselessly monitor and manage ourselves. The growing pressure for people to optimise their free time – for instance, signing up to the work meditation app to manage work-stress – turns our free time into just another aspect of work.

The Whale Ghosts

In Sydney’s wealthiest suburb and erstwhile site of Archibald Mosman’s whaling station, Elias Greig finds himself haunted by the hulking bodies of whales.

In that epic butchery, what airs and fluids were released to seep into the land and water of that place? What sobbed from those lungs in which a man could fit, whose breath had weight and could move matter, its voice like a vast limb? What burst from those cuts, those lurid curtains of flesh parted by knives, the skin peeled back in spirals by the flensing spades?

Money Against Eternity

I ask Mason whether, during this time, he was ever discouraged from gambling. It never happened. He remembers how, in one small venue where the staff knew him by name (to be fair, not a club), 'I would put $50 in the machine, and before that first $50 was through, I would have a beer sitting next to me.'

We Don’t Use Language Like That

A multivocal poem exploring love and relationships through language and silence. The beauty and tension of the poem come from the way the unsaid, lurking in the spaces between the words and lines, exerts a tidal pull on the narrative.

A Teleology of Folding, and of Dying

I stopped offering the folded envelope of my identity months ago and yet still, to hear my name said aloud is a particular thrill; almost sensual, like new touch. The intimacy of it takes my breath away. I glow at its gentle syncopation, the shallow sigh of its vowels. My name is Persian for beloved. Where I am from, it identifies me: Bosniak, and: Muslim.

Learning Bundjalung on Tharawal

Araluen navigates hope and grief as she reflects on the process of learning and reclaiming Language as an adult.

So in this place the shape of my place

I am trying to sing like hill and saltwater,

to use old words from an old country that I have never walked on:

bundjalung jagum ngai, nganduwal nyuyaya,

and god, I don’t even know

if I’m saying it right.

Food Culture in Late Capitalism

So charged is food now with our preoccupations, what we choose to put in our bodies can be read as a contemporary index for who we are and what we want...No longer just an elevated marker of class and aesthetics, in their offer of supreme salvation, these meals are the inversion of contemporary concerns with alienation, the Anthropocene, and the capitalist limitations of the body.

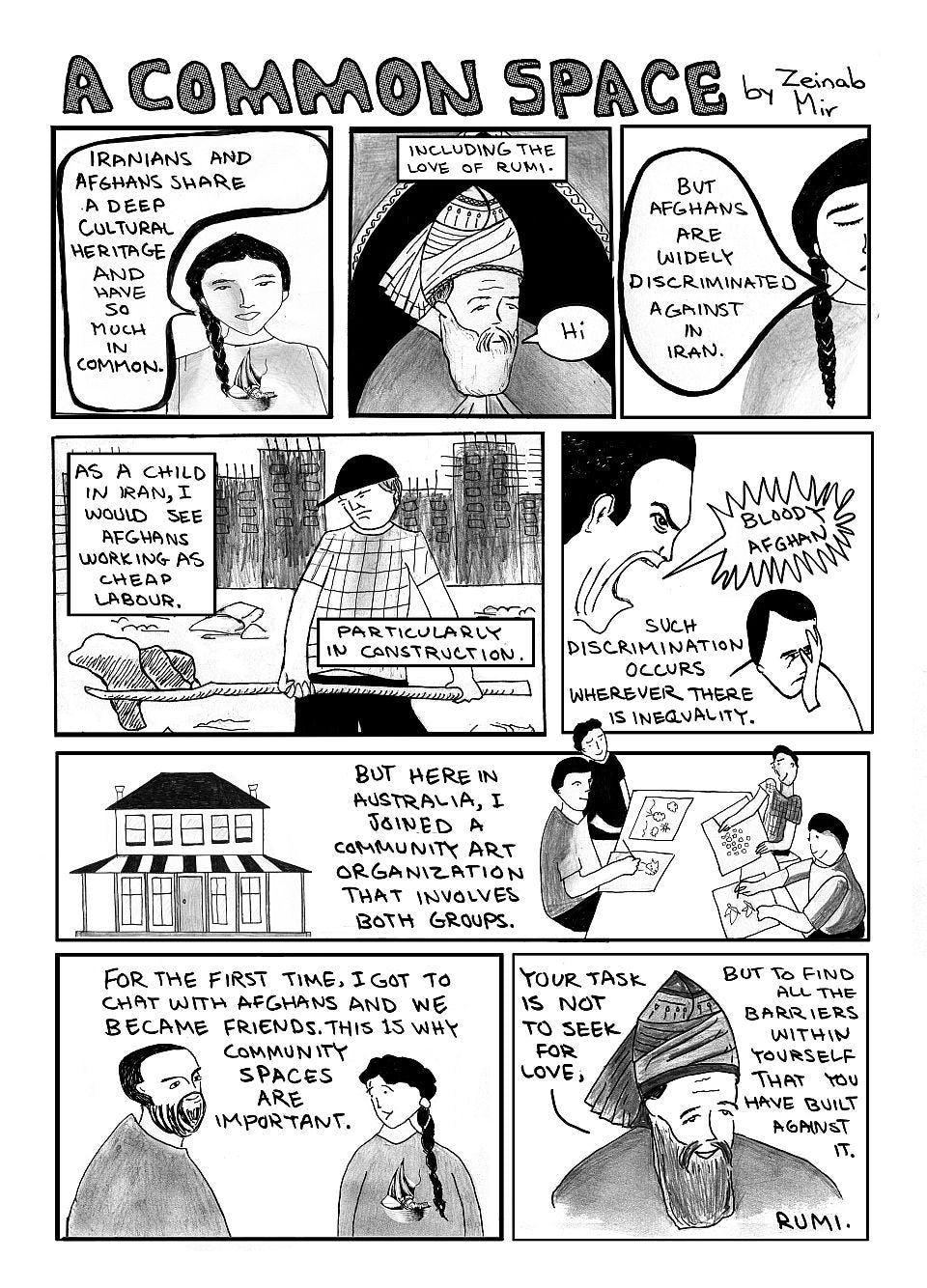

Community / A Common Space

As a child in Iran, I would see Afghans working as cheap labour.

Particularly in construction.

Such discrimination occurs wherever there is inequality.

Writing

I come back to this piece all the time. There’s an aliveness to the rhythm of reading it that I really love – how it traces thought processes, displays uncertainty and pulls off those weird half-jokes that usually only work when spoken aloud.